WELCOME

- SUSAN A MATTHEWS HOME

- SHANTI SCHOOL HOME PAGE

- STUDY GUIDE

- SPIRAL ANATOMY™

- BRAIN WORKSHOP™ TRAINING

- GEORGE XU HOME PAGE

- CONTACT US

Website

Design: Susan Matthews

© 2003-2024

all rights reserved

No part of this website may be reproduced without expressed permission.

On Brain

and Movement:

Mind

and Movement Principles for Enhanced Brain Function, Healing, and Conscious

Evolution

Susan A. Matthews, M.S., August 31, 2007 - 2024

Dr. Susan Matthews is a neuroscientist who has researched spinal cord plasticity, stroke, retina, neuroendocrinology (brain hormones), and dopamine neurophysiology (Parkinsons). Dr. Matthews is an anatomist, biomechanist, a ballroom dancer and a 30-year tai chi master.

Brain Workshop™ Seminars are offered nationally. If you would like to sponsor a Brain Workshop seminar with Susan Matthews please email Susan Matthews at mail@susanamatthews.com.

Brain Workshop™ videos are available for home practice.

Check out the Spiral Anatomy™ Training Course for great packages including

many of these videos. Modules provide stepwise training on major topics!

Check out the Spiral Anatomy™ Training Course for great packages including

many of these videos. Modules provide stepwise training on major topics!

Spiral Anatomy™- Movement and Energy Training for Tai Chi, Sports, Chronic Pain and Rehabilitation

On Brain and Movement: Mind and Movement Principles for Enhanced Brain Function, Healing, and Conscious Evolution

This article is the first in a multi-part series for understanding true mind-body movement integration techniques.

Scientific discoveries about the brain and nervous system have revealed the brain's capability of plasticity — the intrinsic ability to change and grow — to adapt to environmental, physiological and behavioral cues.

Too often, as we turn 50, youthful vigor gradually declines into a slower stiffer, body and mind. Correct exercise has been shown to slow this process in the physical body, and lately much evidence has pointed to the value of mental exercises for keeping the brain youthful. This article presents an approach to maintaining overall health and well-being by using precise movements along with precise mental focus to directly affect the function of the brain and nervous system.

All physical and mental health is dependent primarily on a fine-tuned nervous system yet rarely does physical exercise take this approach. Most of what we see these days is “muscle exercise” with secondary effects on the cardiovascular system and internal organs. Practitioners of Chinese Internal martial arts such as taijiquan (Tai Chi) have consistently used various forms of “meditative” movement to promote longevity. Using proven methods to induce plasticity, formation of new neural pathways can be made by using a multilevel approach to activate the brain for health, healing and even higher consciousness.

Practitioners have cultivated the dynamic qualities found in taijiquan to enhance physical and mental abilities well-beyond normal, and to further their spiritual paths. In terms of rehabilitation, these same qualities make it the "supreme ultimate" exercise to access the brain and to activate the nervous system to change, perhaps even heal itself, through movement.

Similar benefits can be achieved in many other types of exercise if they contain certain mind/movement principles. Running, walking, tennis, golf, and everyday activities can be enhanced.

First, synchronicity, rhythmicity, and symmetry have all been linked to brain activation during memory acquisition and learning, neural information coding, growth and development, states of consciousness, perception and awareness, locomotion, autonomic function, neural repair, and rehabilitation.

Second, mental practice, including visualization and movement imagery, are receiving greater significance for training and for treatment potential. For example, new imaging techniques have shown that imagery, or mental practice, causes neuronal (nerve cell) activity that mirrors actual movement. We also know that movement, respiration and heart rate can be synchronized. This capacity of the nervous system is just beginning to be explored in brain injury research and treatment.

Third, balanced, integrated, left- and right-sided movement is accompanied by balanced brain activity; i.e., accessing the brain's neural circuitry is a direct approach to enhancing function or to healing physical and mental dysfunction resulting from mechanical injury or biochemical imbalance. Balance is accomplished by using two major components of tai chi training 1) central equilibrium training, the concept of developing a straight spine with an energetic central “plumb line,” and 2) the biomechanics of spiraling in the joints, called chan shi chin training.

Fourth, fast progress can be made by engaging multiple sensory systems (visual, kinesthetic, and sensory for gravity and position, muscle stretch and load, skin) both physically and with mind intention. For example: simply visualizing sand filling the feet and legs causes greater stability, heaviness and a downward 'root'. Next, just turning your attention to the top of the head and visualizing an upward motion establishes a plumb line around which all movement and thought is balanced and focused. Mentally shifting sand from left to right, along with weight, sets up a rhythmic movement that can affect brain rhythms.

Fifth, training the mind to 1) increase awareness of the sensation of internal energy (qi) in the body; 2) direct the internal energy to flow in harmony with the physical movement; 3) allow the physical movement to follow the mentally directed energy flow, and; 4) ultimately cultivate awareness of the energetic movement in the space (universe) surrounding the movement.

Synchronized, Rhythmic Movement

Communication between distant brain areas is important for integration of complex information to adapt to changes in the environment and to generate appropriate responses necessary for successful behavior in daily life. Through numerous experiments, it has been established that cortical neurons strengthen their connections by repeated stimulation and synchronous activation — this is called ‘Hebb's Rule’, commonly stated “neurons that fire together, wire together.”

On the basis of this, it has been assumed that perceptions or actions are represented in the brain by large numbers of distributed neurons firing in synchrony. Synchronous activity is often associated with oscillatory firing patterns, rhythms, in discrete frequency bands that represent certain aspects of behavior, learning, common motion, direction and velocity, or coordination. These rhythmic activities are synchronous over relatively large areas of cortex and even deeper brain structures, between the left and right cerebral hemispheres, between the visual and motor (movement command) centers of the brain, and between the motor and somatosensory (what the body feels) centers. They are also enhanced in amplitude when performing new and complicated motor acts.

Information is coded in the brain in different frequency bands. Frequencies in the alpha-band (7–13 Hz) dominate during perceptual tasks and sensory processing, whereas beta-band oscillations are probably more prominent during movement, theta-band oscillations during (working) memory and preparational processes, and gamma-band oscillations to higher cognitive functions.

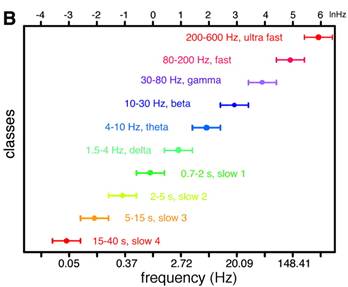

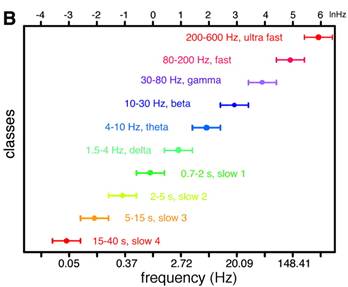

The mean frequencies of the experimentally observed classes form a linear

progression on a natural logarithmic scale with a constant ratio between

neighboring frequencies, leading to the separation of frequency bands.

Neighboring frequency bands within the same neuronal network are typically

associated with different brain states and compete with each other. On

the other hand, several rhythms can coexist at the same time in the same

or different structures and interact with each other.

The mean frequencies of the experimentally observed classes form a linear

progression on a natural logarithmic scale with a constant ratio between

neighboring frequencies, leading to the separation of frequency bands.

Neighboring frequency bands within the same neuronal network are typically

associated with different brain states and compete with each other. On

the other hand, several rhythms can coexist at the same time in the same

or different structures and interact with each other.

Research data on animals and humans shows evidence for the behavioral relevance of slow, i.e. low-frequency oscillations (regular, wave-like variations). They support the concept that slowly oscillating groups of cells comprise large numbers of broadly distributed neurons that are connected with regard to function. Higher frequency oscillations are confined to a small neuronal space, whereas very large networks are recruited during slow oscillations.

Behaviorally relevant brain oscillations relate to each other in a specific manner to allow neuronal networks of different sizes with wide variety of connections to cooperate in a coordinated manner. As a general rule, the neuronal excitability is larger during a certain phase of the oscillation period. The practical application of this information is that slow rhythmic movement (1 Hz or one beat per second) may entrain, control, or balance a vast neuronal network. Thus, the slow motion movements of Tai Chi forms may result in this kind of neural control.

My Wu Style Grand Master Wang Hao Da performed his Tai Chi form with this beat, not only in rhythm with his own heartbeat, but with the “heartbeat of the earth.” In this way, Taijiquan and Qigong strengthen and tune the body so that it becomes like a violin string. When plucked by the mind, it is able to transmit energy with vigor--for health, for healing, for spiritual wisdom.

It is possible that activation of altered states of consciousness experienced as a “runners high,” during drumming and dancing rituals, Tibetan Buddhist chanting, or esoteric practices such as Sufi dancing activate brain processes through such a mechanism. Likewise, the comfort imparted by rocking and walking my daughter’s new baby, or the incessant kneading and purring of my cat, or the well known benefits of therapeutic riding for developmental disorders, suggests the power of rhythmic movement. It also suggests that tremors and epileptic seizures could be a result of the loss of the superimposed slower rhythms. For example, the tremor developed in advanced stages of Parkinson’s Disease may be, in part, be due to a loss in basal ganglia (a deep brain structure) rhythms in dopamine neuron activity.

Tai Chi forms are designed with slow rhythm, with all joints synchronized in their movement pattern, globally integrated by intent and awareness of the global movement of qi.

The second through fifth principles will be covered in the articles that will follow in the series. The ebb and flow of neural activity is mirrored in the wavelike flow of qi in the body which itself is at the same time resonance at a higher frequency.

Susan A. Matthews is a Master of Chinese Internal Martial Arts, founder of the Shanti School of Taijiquan in Durango, Colorado and has practiced and taught Tai Chi and Qigong for 25 years. Neuroscientist, anatomist, biomechanist, and researcher in neural networks and neuroplasticity, spinal cord development, stroke rehabilitation, Parkinson's and pineal neurophysiology, she integrates Western scholarship and research in neuroscience with Chinese Internal Martial Arts training. She has just spent the last four years in a Ph.D. program in Cell and Neurobiology at the University of Southern California. She studies and teaches various internal martial arts styles, including Wu and Chen styles of Tai Chi, Xing Yi, and the Lan Shou System. She is certified in the Mi Zong School of Medical Qigong.

Figure shows the progression of distinct frequency bands that are dominant

in the nervous system. (modified from Penttonen, M. and Buzasaki, G.,

2003. Natural logarithmic relationship between brain oscillators. Thalamus

& Related systems).

Figure shows the progression of distinct frequency bands that are dominant

in the nervous system. (modified from Penttonen, M. and Buzasaki, G.,

2003. Natural logarithmic relationship between brain oscillators. Thalamus

& Related systems).